In the early hours of Halloween morning, 1920, Albert Boyer and Leo Goodman watched the last trolley cars depart from the steps of the Payne Avenue Junction waiting room where they worked. A few sparks fell from a trolley pole and briefly illuminated the crossing wires of the overhead contact system before darkness retook the street. Although it was late, the trio still had some fun planned: their friend, 21 year-old Chester Martz (who had served in a WWI Tank corps and lived just down Paynes avenue) had arrived in his sidecar-equipped motorcycle to take them all for a spin around North Tonawanda. “It would be an ideal night for some real excitement!” one quipped.

Martz and his crew drove toward the desperate cries.

The cycle and sidecar roared down Niagara street, and careened east down Schenck street. (After his stint in the military, Martz never seemed to get the hang of civilian driving: He had been arrested for speeding less than a month before, and would tragically die in an automobile accident the following year). While heading south on Division street, the three men suddenly saw a burst of yellow flame and black smoke in the sky above the embankment of the High Speed Line that bisected the city. Martz was worried – the flames seemed to be coming from the Tonawanda Power company’s Robinson street plant, where his older brother Stanley worked. They hurried to the nearest signal box to alert local authorities to the fire. Then, above Martz’s motorcycle’s idle, they heard the screams of multiple men in the distance: chilling, tortured screams; begging, pleading for help.

Martz and his crew drove toward the desperate cries. They would be the first on scene to the deadliest night in the history of the Tonawandas. They were about to get their excitement – and then some.

Upgrade, interrupted

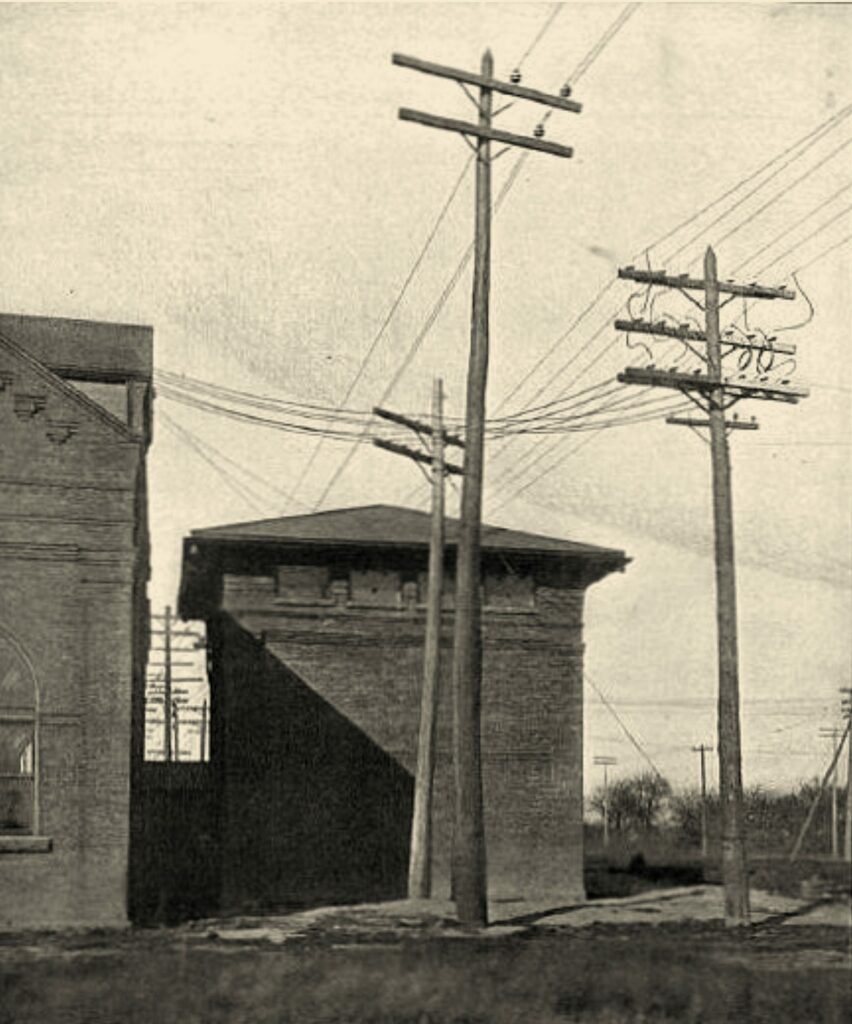

A few minutes before, at the nearby Tonawanda Power company plant on Robinson street, a group of thirteen electrical engineers and employees (four from the Tonawanda Power company and nine from the Niagara Falls Power company) were finishing the installation of two powerful new transformers. The old transformer building on the east side of the property was a key piece of a transmission line carrying hydroelectric power from Niagara Falls to Buffalo 24 years before. The new 45,000 volt Westinghouse transformers would more than double the sub-station’s transmission capacity.

Feeling that all was prepared, the signal was given to the Niagara Falls Power company to restart the current that had been turned off at 1 a.m. The employees assembled in the switching tower (a roughly 20′ square, 2-story building that stood where the new “pocket park” is), where they would be able to meter the power being delivered to the new units.

The Tonawanda News describes what happened next:

The test was in progress seven minutes when a sizzling noise was detected coming from the transformer meter box. Orders were given to shut off the switch. [Derby] started forward to throw the switch lever. As he was extending his hand toward the lever there was a terrific explosion followed instantly by the ignition of the oil which was used for cooling the apparatus.

Tonawanda News, 11/1/1920

The cooling oil was stored in wooden troughs under the transformers. The spraying accelerant mostly covered the men’s lower arms and legs. Four of them died instantly as the small switching tower became a nightmare of burning oil and flames. One or two jumped (or were propelled) out of the tower’s windows, which were all blown out with the force of the blast. Three made their way out of the tower and transformer house. The bricks of the tower’s west wall bulged. In the plain words of a national trade, “Everything which could burn, short circuit or blow up did so” (Safety Bulletin).

The survivors

Chief engineer Albert S. Allen (who had heard the sizzling noise and had in vain given the order to stop the current) was one of the employees who made it out of the buildings. Like all the others, he was horribly injured. According to one account, “With only one shoe and part of his collar intact among the shreds of what had once been his clothing, he staggered out of the raring tower to the telephone, and called up the powerhouse to shut off the current. On his hands and knees he tried to crawl back again to help [Samuel] Derby bring out the helpless…his first thought was for the safety of his station” (Safety Bulletin, 1921).

Samuel Derby, Line Foreman for Niagara Falls Power company, was blown out of the tower’s second-story window, but put out the flames racing over his body by rolling in the dewey morning grass.

He returned to the blaze and dragged six men out of the worst of the fire. The scene was chaotic:

Men ran from the building with their hair and little of their clothes in flames…Others…extinguished the flames in their clothing by rolling in the grass and dew of the morning…They rushed into the flaming doorway with their clothing afire, their shoes and hats burning and hair and beards white with the intense heat. They were helpless on the floor within [seconds,] in agony from the burns. The screams of the men were terrible. It seems a marvel to those who witnessed it that the men were able to stand up and try to put out the flames which all seemed to start at the same time on their bodies and heads.

“12 now dead in blaze,” Tonawanda News, 11/1/1920

20 year-old lineman Edward Shamrock, no doubt in shock at the horrifying and unexpected turn of events, scaled the High Speed Line embankment and ran half a mile to his home on East Robinson before being recovered and taken to DeGraff Hospital for treatment. Martz would later testify, “He was jet black except one white spot around one eye, and as if he had put his hand over it or something and didn’t get burned. His clothes were nearly all off.”

In spite of the best efforts of nurses and electrical burns specialists who came to help, within 24 hours, eight more men would succumb to their debilitating injuries, leaving just one of the thirteen employees present at the cutover alive.

Hero Samuel Derby the last to succumb

The thirteenth man, Samuel Derby (who had rescued six men) seemed to have a fighting chance at survival. The morning of the fire, he was actually driven home to 222 Niagara Street in Chester Martz’s motorcycle sidecar, and left in the care of his wife, Rose. Two days later, however, his condition remained critical enough that physicians ordered his removal to DeGraff hospital. Doctors were summoned from Buffalo and Rochester to consult in his care. On November 4, he was interviewed by Coroner Wheeler (Albert S. Allen had also made a statement). That day a case of hiccoughs seized the unfortunate Derby, which could not be stopped. He died the next morning. Many believed if he had not returned to the burning building to help the others, he could have survived himself.

Every man who had been on hand to activate the new transformers, from the engineers of the Niagara Falls and Tonawanda power companies, to the night shift workers, was now dead. The superstitious could not fail to notice that they numbered thirteen.

Leave a Reply