Everyone in North Tonawanda knows the Wurlitzer name: The jukeboxes made here brought worldwide fame to our city, and provided livings for three generations. The iconic tower on the boulevard reminds us of this legacy every time we drive by (or have to run to Wal-Mart real quick for tube socks).

But behind the tower, out in the heap of old buildings, on a placard high in the air, is inscribed a less-familiar name. It does not blaze forth in red light across Sawyer Creek as “Wurlitzer” does nightly, and yet, without it, there would have been no Wurlitzer here. The name is “Eugene de Kleist.”

The Offer

NORTH TONAWANDA, New York. November 1892. Armitage-Herschell & Co. plant, Oliver and Mechanic Street.

Eugene de Kleist steps down briskly from the carriage, setting his fine leather shoes onto the dirt road.

It is 1892, and de Kleist has come all the way from England to talk business. His hosts are a pair of Scottish brothers, Allan and George Herschell, and an Englishman, James Armitage. Their firm, the “Armitage-Herschell Company,” has enjoyed great success over the past twenty years making and selling steam-powered entertainment machines called “riding galleries,” or “merry-go-rounds.” They lead de Kleist through a welter of sooty workshops on their property at Oliver and Mechanic streets (today, the Carousel Apartments).

The German gentleman strokes his fashionable mustache impatiently as he eyes the brass and iron foundry, the smithy, the engine and boiler works. The group navigates a wooden footbridge spanning the muddy stream of the “State Ditch.” In one building, craftsmen are carving and painting the life-size horses and fantastical beasts that give the merry-go-round its heroic power–and make it a reliable fairground moneymaker. By now a small crowd of workmen has gathered to gawk at the refined stranger from overseas.

“And the organs?” de Kleist asks.

George Herschell tells two boys to roll open a warehouse door. “This is all we have left.”

Sunlight floods into the dark interior of the warehouse, and reveals scores of festive musical organs of every shape, size and color, waiting to be shipped with carousels. There are simple “military band” organs with just a row of pipes and a drum or two. There are giant, glittering orchestrions outfitted with pipes, xylophones, trumpets, percussion, and (for now) motionless marionettes. De Kleist recognizes some Limonaire Freres organs he has personally sold the firm from his store in London.

Allan Herschell can no longer conceal his excitement. “So what do you say, Herr de Kleist? Will you come here to build our organs? As discussed, we cannot afford to continue importing them from Europe with the new tariff laws, and we have ample land. Lumber materials are as abundant as the air here, and your factory will be advantageously located near rail. You will have the organ industry to yourself in North Am–“

“The gentleman understands all the particulars, and can decide at his pleasure of course,” the older partner James Armitage offers diplomatically.

De Kleist’s gaze returns to the organs. He bows his head in contemplation of the possibilities. The terms are agreeable: He will have an option to take full ownership of the factory after one year, and while making band organs for carousels will be his main business, he is free to take other clients if he can find them. The skills for building organs are almost unknown here, but he can import prefabricated parts from Europe until his workforce is trained. Perhaps best of all, with a three-story factory and his own extensive expertise, he will finally have the resources to build organs to rival, if not surpass, those of the great European makers.

When de Kleist he raises his head, his smile is as wide as the brim on his bowler hat.

“I will do it, gentleman. I will move my family to America.” He gestures toward the carousel horse carving building. “We will hitch our fortunes to your painted horses.”

The nucleus of Wurlitzer: de Kleist’s North Tonawanda Barrel Organ Factory

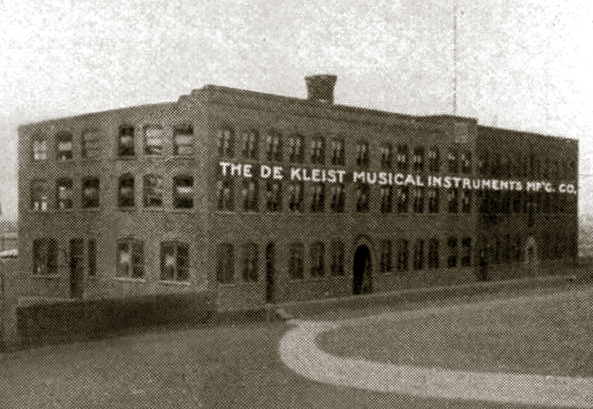

“Just on the outskirts of North Tonawanda, awaiting with confident expectation the onward march of time to raise it from a little hamlet to more pretentious proportions, stands the pretty suburb of this city, Sawyers Creek, or more properly East avenue, and here, like a pioneer on the edge of civilization, is located an elegant three story brick structure of handsome appearance over which the stars and stripes float gaily on the breeze. The commodious home of an industry comparatively unfamiliar to the great majority of citizens, but already attaining a world wide reputation under the name of the North Tonawanda Barrel Organ Factory.“

Tonawanda Evening News, January 4, 1894

In the spring of 1893, Armitage-Herschell build de Kleist a factory.

The enterprise is dubbed the “North Tonawanda Barrel Organ Factory,” and it is the nucleus of today’s Wurlitzer campus.

The German language rings in the air in this neighborhood just south of Sawyer’s Creek called Martinsville, and that suits de Kleist just fine. He brought a few craftsmen with him from England, but mostly he teaches farmhands, machinists and carpenters the Old World trade of organ building. A lavish Queen Anne home is added near the factory for the growing de Kleist family to live in, on what is aptly named “Organ Avenue.”

For its day, it is a top-notch facility: A 45-horsepower engine and boiler provides both steam heat and motive power. A main shaft turns belts and pulleys throughout the factory, which drive the saws, lathes, boring and other machines to be used in organ construction. Some of the machinery has been invented or modified by de Kleist. Since it will be a few more years before electricity is widely available in the city, an onsite Westinghouse dynamo provides electric lighting.

The main shaft starts on June 20, 1893 (five days after de Kleist’s return from Europe). That same day, the factory takes in a $1,000 Paris organ for repairs, earmarked to accompany an Armitage-Herschell carousel that will circulate through Kansas.

Fifteen employees are on hand at the beginning. By winter 1893 the force has doubled, and they are turning out about an organ a week. De Kleist expects that by the following summer they will be running at full capacity, with 200 hands producing organs at a rate of one every day. This expectation of de Kleist’s proves to be wildly optimistic.

Introducing the Wurlitzers

The national economy is hit hard by the Panic of 1894: thousands of businesses fail, and by 1897 the North Tonawanda Barrel Organ Factory is down to just 12 hands. De Kleist begins looking for other business, when he makes a fateful connection with an ancient musical family, the Wurlitzers.

Farny Wurlitzer (who, incredibly, ran the North Tonawanda plant from 1909 to his death in 1972), tells how they met de Kleist and fell into business in this 1964 speech:

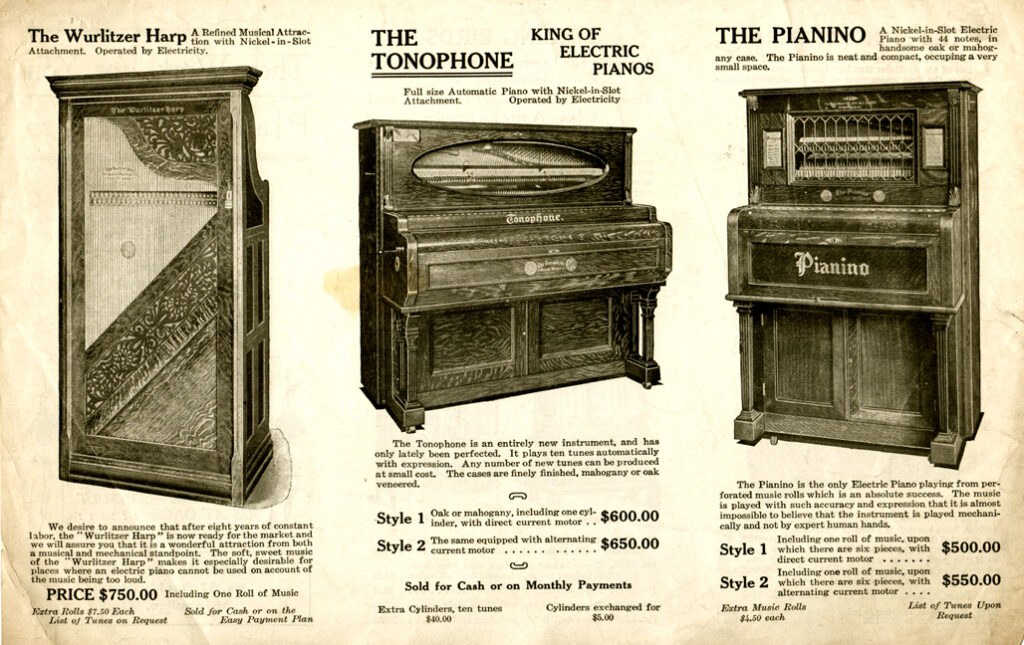

The business association with Wurlitzer begins in 1898 with the production of 200 coin-operated player pianos (“The Tonophone”). Once this joint venture becomes a success, Wurlitzer requests de Kleist build additional instruments, tapping into his band organ skills, and his German genius for clockworks and fine machinery.

De Kleist cashes out

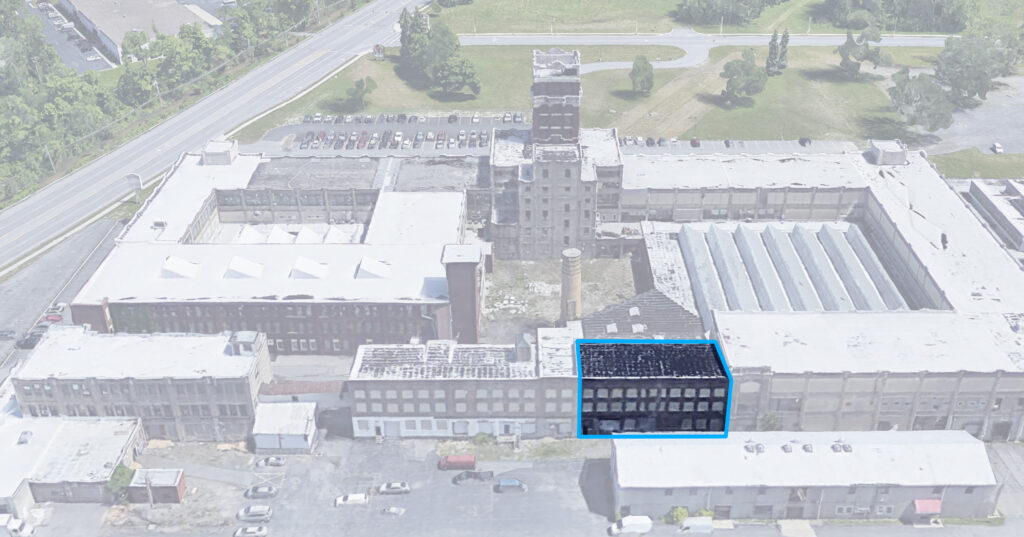

The long-stagnant organ factory out on the creek road triples in size in 1902, and is renamed the “De Kleist Musical Instrument Manufacturing Company.” A placard is hoisted in place to mark the accomplishment. After 10 years of effort, the factory has become prosperous. De Kleist moves his family to a new home on the city’s prestigious Goundry street. He throws his hat into local politics, becoming mayor of North Tonawanda. He races power boats, a fashionable, thoroughly modern and rather expensive gentleman’s pursuit on the rivers and streams of the day.

Some say he becomes lax in his business. Rival band organ and automatic musical instrument companies spring up, largely comprised of disgruntled former employees. He files a lawsuit against one, the North Tonawanda Musical Instrument Works, on Payne avenue. When her returns from a vacation in 1908, he discovers his foreman has been stealing from him. On top of all this, his health is suffering. His business position suddenly becomes more precarious. This makes the Wurlitzer family–who have invested heavily in the German inventor–very nervous.

So, in 1908, Wurlitzer suggests a merger. De Kleist stays on in honorary capacity, his son August on the board.

A Spanish exit

His health failing, Eugene de Kleist returns to Europe in August of 1910. He dies three years later, while vacationing with his mistress in Biarritz, Spain.

Go see for yourself

The barrel organ factory and placard are still there, in plain sight. The building is being used, after a fashion–a zombified husk. I am told the 130 year-old wooden floors on the ground floor are warped and unwalkable. The red brick exterior has been caked in concrete to keep it from crumbling, and the windows are sealed with sun-blanched plastic. The bottom floor has been gouged by large automatic doors. Strange to see the place still standing, a specter out of its time, and to remember the hopes and disappointments that mingled here, in what is now a mostly forgotten back lot.

Leave a Reply