Sometimes a place name can be on the lips of generations, and then just…disappear.

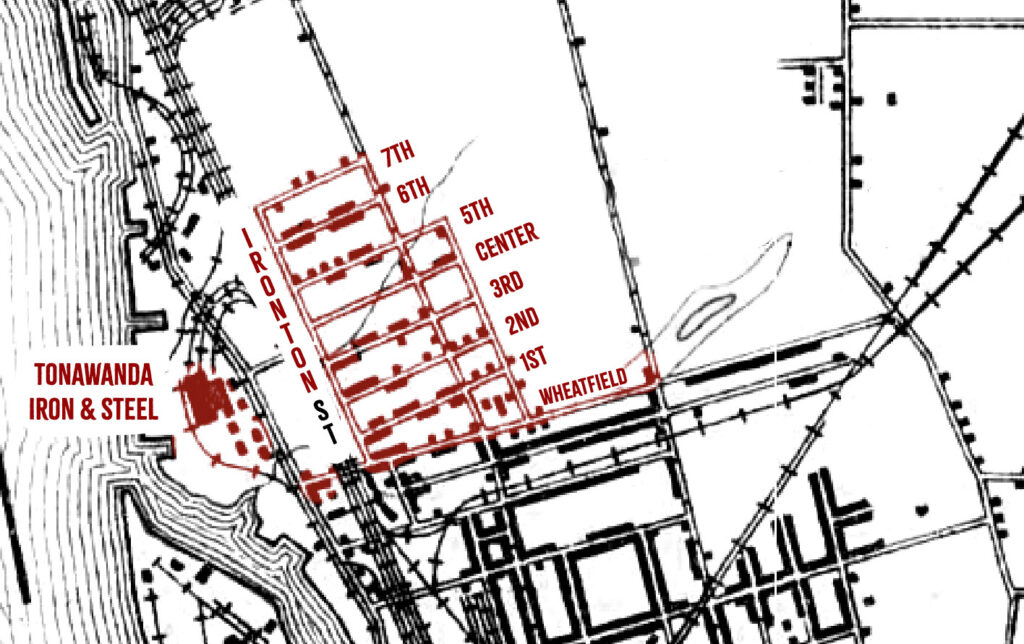

Such is the fate of “Ironton,” the name of a working-class neighborhood and industrial tract that laid just north of the original Village of North Tonawanda. Its name graced schools, businesses, sports teams, and headlined a Tonawanda News section. Yet, unlike other nearby districts Gratwick and Martinsville, Ironton is now largely forgotten, surviving only in the name of “Ironton Street,” a leafy, junk-strewn, half-mile stretch near the river.

But Ironton’s story is more than just the disappearance of a place name—it is the story of the emergence of The Avenues and an industrial force from the farms and marshes north of Wheatfield Street in the 1870s.

Let’s have a look at Ironton’s origin, its vanished landmarks, and how its legacy shapes the community we know today.

1873: Iron on the river

“As the ruddy flames leaped up higher and higher in the big furnace, a message went out to the city waterworks. In a moment the fire whistle there was shrieking as if the whole city were on fire. That was but a signal. From North to South, from East to West, every steam whistle in the Twin Cities, every whistle on the steamers and tugs in the harbor, was opened to its full capacity. Shrieking, bellowing, roaring, the tremendous voice of resurrected, happy industry saluted the event of the day and the man of the hour. Never before in the Tonawandas, and perhaps in no other city, was there heard such a bellowing of joy.” – On the firing of the brand-new Tonawanda Iron & Steel furnace by brand-new President-elect William McKinley; Tonawanda News, November 8, 1896.

You could say Ironton was born in fire.

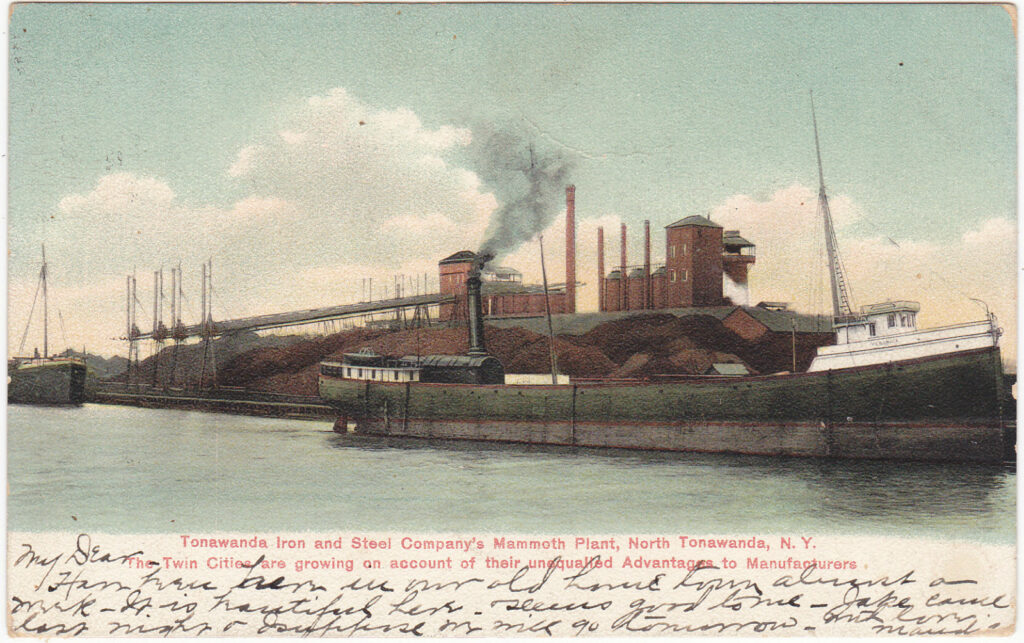

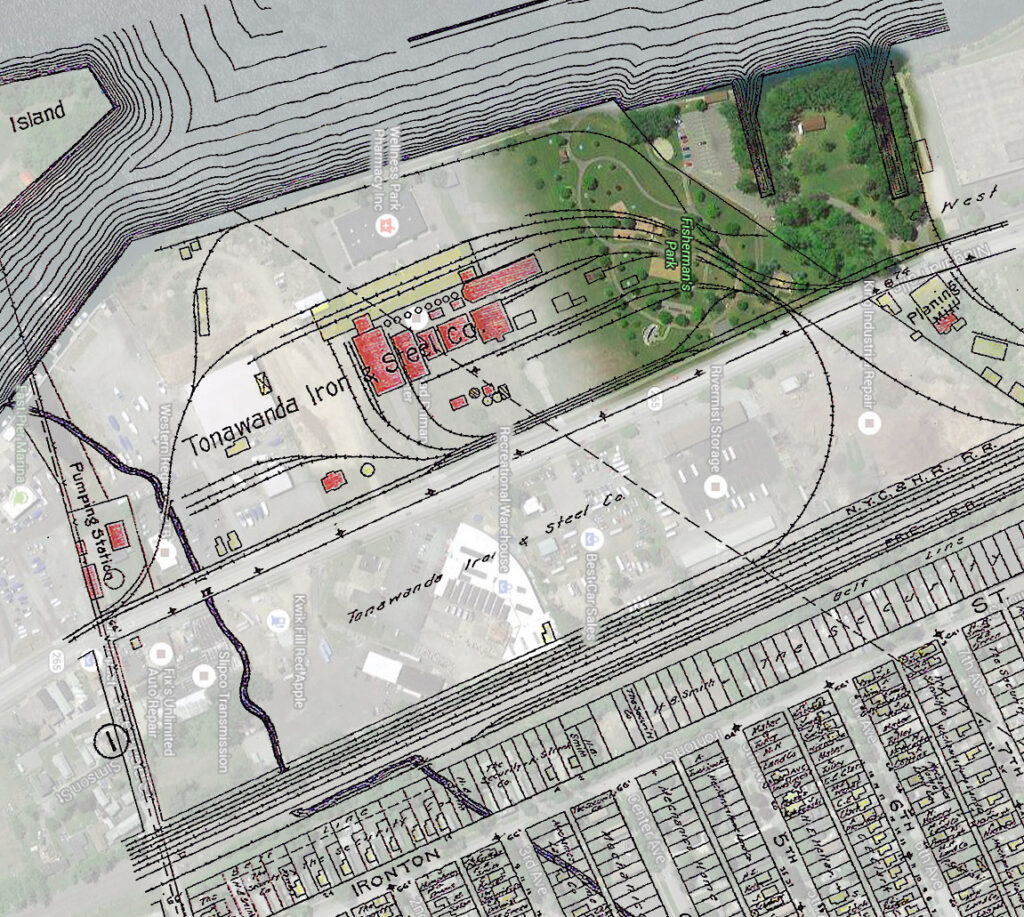

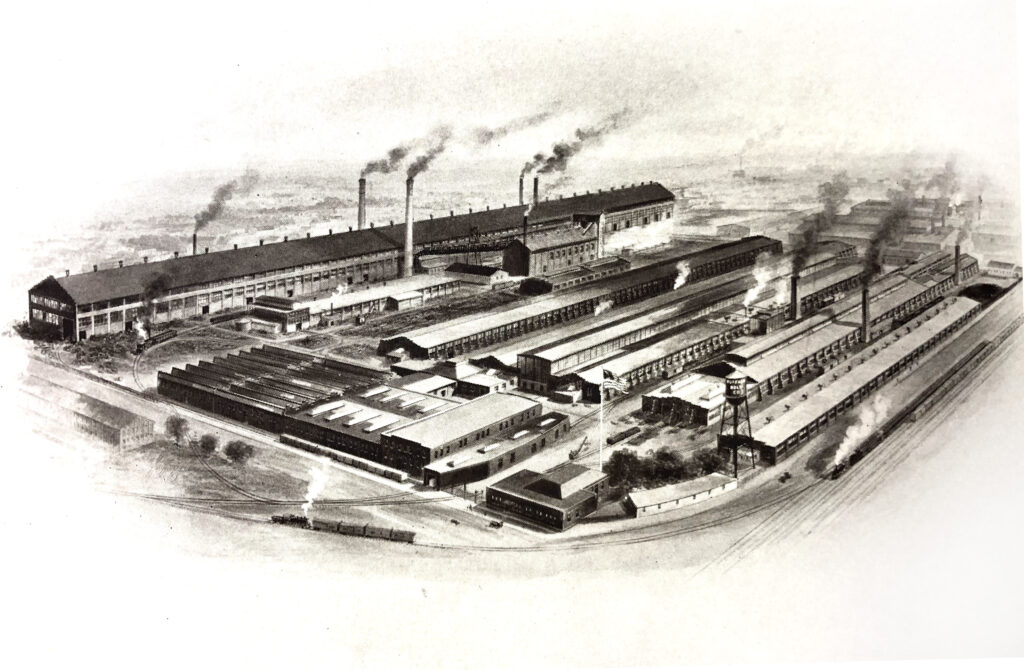

In 1873, the Buffalo-backed Niagara River Iron Company establishes a blast furnace on the Niagara River, north of Wheatfield Street. The river location is advantageous: the fifty tons of pig iron the works is expected to turn out daily can be loaded directly onto lake vessels for shipment to the Midwest.

Although the company closes after only a year, Tonawanda Iron and Steel purchases, renovates and re-opens the works starting in 1889. They add 450 jobs in 1896 alone.

For decades to follow, the blast furnaces and slag pits from the iron works on the river will cast “a beautiful ruddy glare on the sky in the direction of the Ironton district,” nightly evidence of the literal engine of prosperity, still remembered by some of our city’s elder statespeople. (“Rainbow of Promise,” Tonawanda News, November 6, 1896).

Ironton Land boom

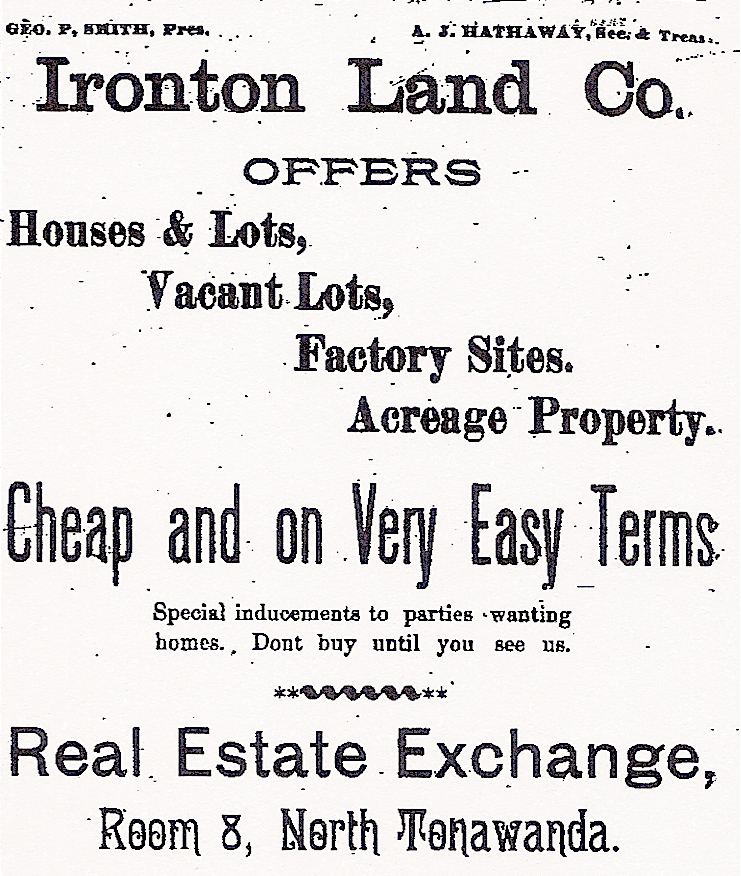

In recognition of the prosperity the iron works is hoped to bring to the region, real estate speculators name the adjacent area (part of the Town of Wheatfield at the time) “Ironton.” The name is likely a nod to Ironton, Ohio, another village near a foundry on a river.

The North Tonawanda Land Co., the Ironton Land Co. and others purchase the land from previous investors and local farmers, including the Carr family, whose name is memorialized in Carr street. The re-platted lots are offered to both residential and industrial customers.

An industrial corridor

After the iron works arrives, additional manufacturing concerns locate here in the early 1890s, including: Plumb, Burdict and Barnard (later Buffalo Bolt), Buffalo Pumps, Gillie, Goddard & Co. (who make merry-go-rounds and bicycles on Oliver near 15th), and the short-lived, tragedy-plagued Boulton Carbon Mfg Co. (on 17th). The generally favorable conditions for industry are described in an 1891 guide book to the Tonawandas:

The Ironton addition is less than a mile from the North Tonawanda City Hall…This section of the city will make a convenient and desirable place for mechanics and business firms. It has the water supply, electric lights, and will soon be connected by the electric street car line.

North Tonawanda and Tonawanda – The Lumber City (1891)

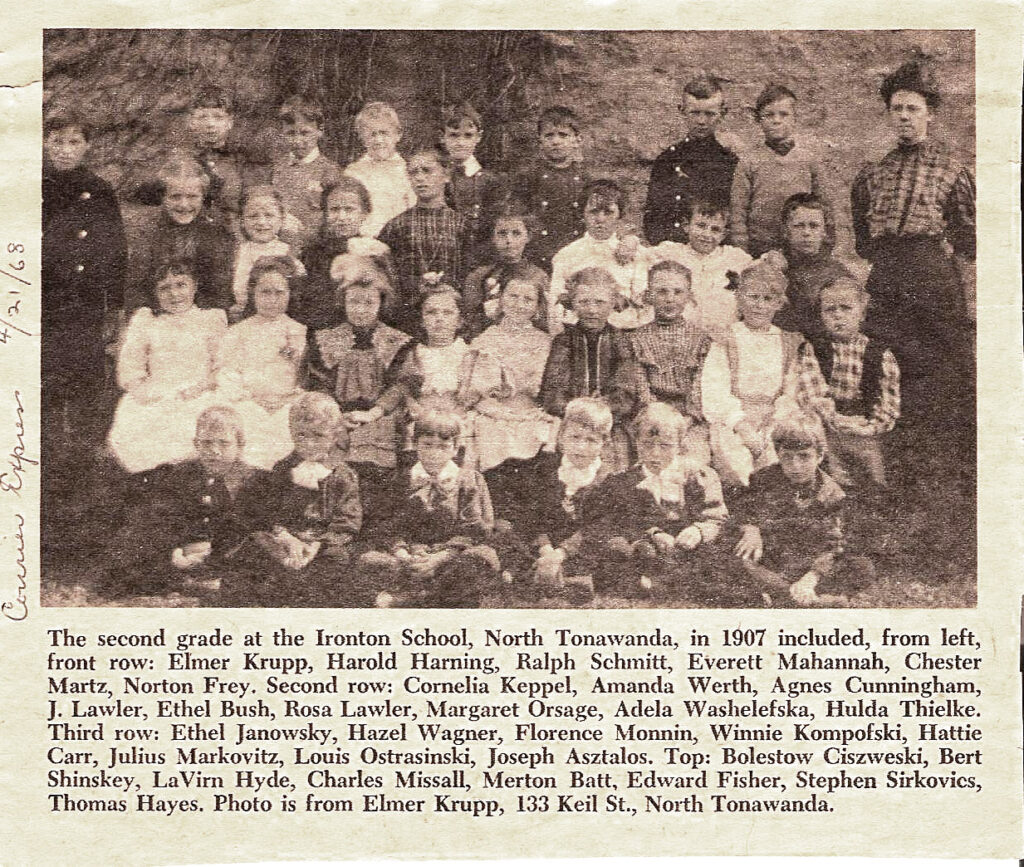

Poles, Hungarians and others flock to the affordable land and job opportunities, bringing their languages, traditions, and often chickens with them. As Ironton’s avenues begin to fill up in the 1890s and 1900s, Oliver Street (named decades before for Grand Mason Francis J. Oliver) emerges as the community’s main business street. Schools are added to help educate the area youth, and night classes are offered to teach the adults English.

A rowdy reputation

Fairly or not, Ironton soon gains a reputation for unruly behavior, drawing the ire of local police and public health authorities.

Robberies are common enough, and the specter of violent “gangs of Poles” is frequently invoked in the News. In a typical 1914 article, “notorious Ironton character” Patrick Zelinski of 141 7th Ave is shot dead while attempting to rob a (stationary) train car. “No man in the Ironton district was more feared than Zelinski,” a resident says after the incident. The article continues:

Freight cars have been broken into in the local freight yards with such frequency of late that detectives have been detailed to apprehend the offenders. Last night was the second night that [Detective] Griffin had been stationed here.

“Car burglar shot dead by railroad detective.” Tonawanda News, June 4, 1914

The language barrier between authorities and the Poles and Hungarians doesn’t help matters. When an Irontonian is finally identified and hauled in for questioning, whatever English skills they possess often evaporate like the alcohol in their stills.

Indeed: “Ironton moonshine” is a very profitable and popular commodity in the Tonawandas and beyond during Prohibition. At least one Ransomville farmer enjoys it enough to trade pickles for it until he is, himself, properly pickled. The newspapers of the day are filled with stories of exploding stills and raided taverns and homes on the Avenues.

During the deadly Spanish Flu epidemic (1918-1919), authorities bemoan the stubborn ignorance of the primitives in the “foreign-settled” district, who appear reluctant to call doctors when new cases appear. When quarantine breakers “uptown” are discovered, Dr. Barnard of the Board of Health asks condescendingly in a News interview, “What can we expect of Ironton, when supposedly intelligent and well informed people in vicinity of Goundry street school do not obey quarantine?”

Evidently, not even monkeys are safe in Ironton. An amusing 1898 item tells the story of some primate pestering that escalates quickly:

“I shoota de man who teasa de monk,” shrieked Tony Sando, an Italian organ-grinder, as he wildly flourished a revolver in front of a crowd of men and boys in the Ironton District last night.

Sando came from Buffalo yesterday afternoon to entertain the inhabitants of the lower section of the city with his music and monkey, but it seems that the boys who collected around his organ took more interest in the monkey than they did in the music. They pinched its tail, pulled its ears and did everything possible to make life miserable for the little beast. At last Sando became exasperated and drew a revolver on the mischievous crowd. Patrolman Kinsley appeared on the scene at that stage of the proceedings and immediately attempted to take the weapon from the Italian. Sando resisted, however, and threatened to shoot the officer. After a short struggle he was handcuffed and locked up in the police station in Thompson Street to await trial before City Judge Watkins. When arraigned in the city court the prisoner was fined $5 and after his revolver was returned to him he was ordered out of town.

Buffalo Express, July 3, 1898

Ironton Schools

In 1884, authorities establish the first school in Ironton, at Wheatfield and Dahlgren Place. In that year’s annual report of the New York State Superintendent of Public Instruction, it is described as:

“…a small frame dwelling house, located half a mile from the stone building [Editor: the Goundry street school], rented by the school board, and occupied by about sixty pupils in charge of one teacher. This was, and still is known as the Ironton school.

In 1889 or 1890, the much larger Ironton Public School #2 opens nearby at the corner of 1st Ave and Oliver Street. It is an imposing, Richardsonian Romanesque-style red brick building. In later years it hosts night classes, BOCES, and finally serves as a local doctor’s car garage. Today, it is the site of the Elizabeth Harvey Apartments.

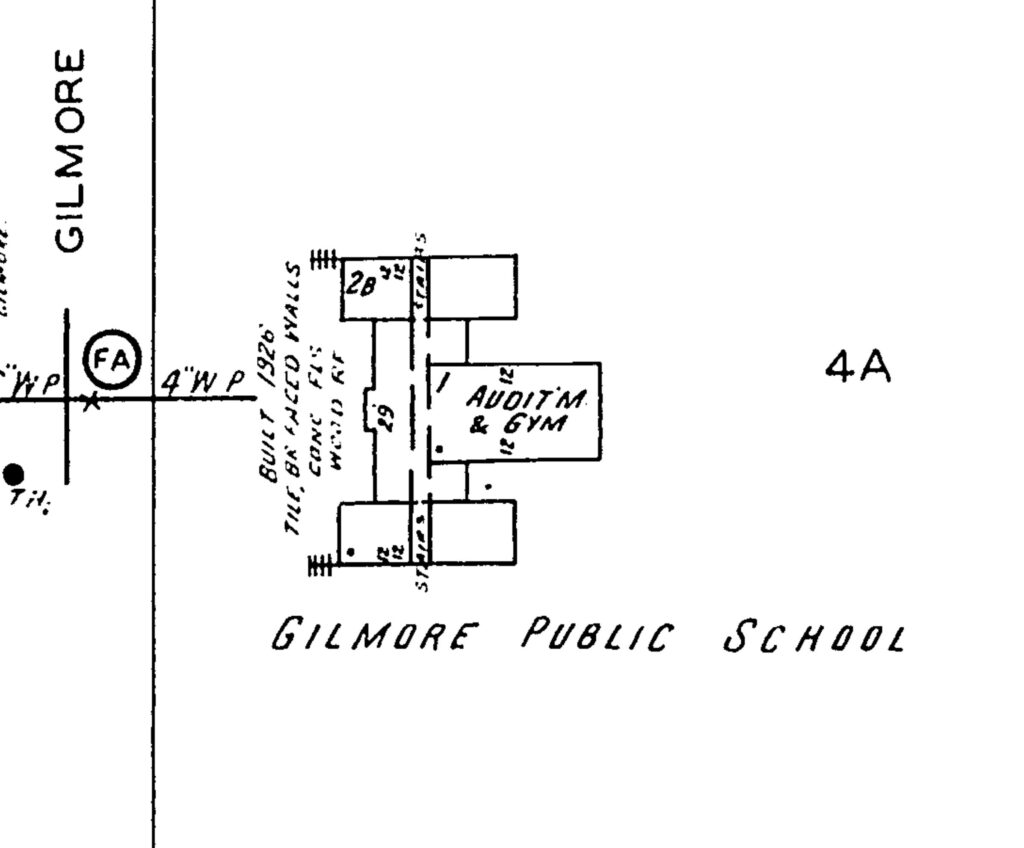

In 1923 the population is exploding as avenues past the original seven continue to be added and settled. Public officials urge a new Ironton school. This will eventually become Gilmore School, Public School No.7, which opens at the east end of 10th Avenue in 1926.

Ironton churches, a silent movie theater and a social club

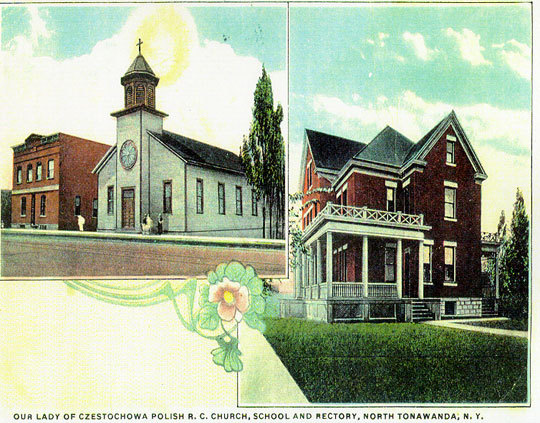

In 1901, a Polish congregation, Our Lady of Czestochowa Parish, is established here. The congregation raises funds to purchase a former Presbyterian church on Oliver Street near Center Avenue, where the grotto is today. Nine years later, Hungarian worshippers establish a church (which still stands) at First and Oliver. On the northwest corner of First and Oliver, in 1914, a silent film and vaudeville theater called “Dreamland” opens. The building quickly becomes a hub for fundraisers, concerts, and other meetings of the surrounding citizenry (today, it is known as the Strand Theatre). Ironton residents will enjoy a full-fledged social club when, on December 5, 1921, the Harmonia Singing Society merges with the Knights of St. Casimer to form Stow. Obywateli Domu Polskiego, Inc., or Dom Polski.

Other organizations with the “Ironton” name

The village was distinct enough for the Tonawanda News to create a regular column, “Ironton News,” to share news of the vicinity. Many organizations are named in the old news pages bearing the community moniker: The “Ironton Athletic Club,” which meets in the Public School No. 7 gymnasium (later “Gilmore School”); The “Ironton Juniors” football team (1914); O.L.C.’s baseball club is nicknamed the “Ironton Nine;” and firefighters Active Hose Co. No. 2, while headquartered on Robinson street, go by the unofficial name “The Ironton Boys.” An “Ironton Hardware Company” is mentioned in a 1931 news item.

The end of Ironton

The Ironton, Gratwick and Martinsville settlements are incorporated into the City of North Tonawanda in 1897. “Ironton” as a place name does not vanish overnight, but slowly fades away over the next half-century. Although its most conspicuous landmarks, Tonawanda Iron and Steel and the Ironton Public School, are long gone, the main features of the original village remain intact for decades: Polish culture thrives on the Avenues, and the hard-working, arguably harder-drinking, industrial character persists with Buffalo Bolt (later Roblin Steel), Buffalo Pumps, Gillie Machine Company, and others. The upper avenues (especially away from Oliver Street) remain mostly marshes and commonly-used farmland until the 1940s, when their settlement accelerates with the nationwide post-war “Baby Boom.”

Ironton may have never had its own post office or official government, but it had a culture and a story all its own, and that story may yet be read in North Tonawanda’s numbered Avenues.

More on NThistory.com

- Avenues / Ironton (neighborhood)

- Avenues Folk (Mary Kijowski-Konstanty, 47 15th Ave.)

- Buffalo Bolt / Roblin Steel

- Buffalo Pumps

- Ironton School

- Our Lady of Czestochowa

- Tonawanda Iron & Steel

Leave a Reply